Our Speciation Event

Cultivarium is open for business as a Frontier Research Contractor

Cultivarium is turning 5. And we’re evolving to double down on our niche.

This has been an unusual journey from day one: non-model microbes, non-model roles, and non-model structure. Yet our team has pulled through challenges that sometimes had nothing to do with science itself.

I’m incredibly proud of the work from this group of intrepid scientists and engineers who have come on this journey. One achievement stands out: while it took us six months to find space during the Great Lab Space Glut of 2020, we only needed a single year in the lab to deliver our two-year milestones with overwhelming success. Since then, we’ve made it our baseline to over-deliver, ahead of schedule, while being under budget. We started from scratch—no existing platform, no tools from academia—and in record time we have produced a slew of public assets including preprint manuscripts, plasmids, code, protocols, and data.

The early years of a new scientific organization are not unlike working with a non-model organism: you don’t really know the growth curve, the stress responses, or the quirks of the environment until you’ve lived in it.

We’ve lived it. We’ve run the first experiment like this in the world.

And now, as we enter our fifth year—alongside a new three-year program with the Wellcome Trust that kicked off this past May—we’re ready for our speciation event.

The Long Arc: How We Got Here

My vision for Cultivarium started long before the organization existed. I studied electrical engineering as an undergraduate and jumped into biomedical engineering for my PhD with Jim Collins—learning computational systems, and synthetic biology while still holding onto the stylings of an engineer. Later, in George Church’s lab, I built engineering frameworks around new enzyme-based technologies and turned Vibrio natriegens from a curiosity into a genetically tractable speed demon.

These experiences taught me something crucial: straddling the disparate fields of biology and traditional engineering could be powerful—and excellence at their intersection necessarily takes time.

During the pandemic, I was part of an incredible team that stood up, from scratch, one of the fastest and largest clinical-serving labs with industrial-grade lab automation—PCR testing and viral sequencing at a scale I hope we will never need again. I loved every exhausting minute of it: the urgency, the scale, the mission. It showed me the convergence I’d been building toward: a way to bring this intensity to unblocking the bottlenecks that hold biological research back.

Those years collectively were Step 1—or 20 years of my life—of a longer trajectory I didn’t yet have a name for.

Step 2: Build the Tools for the 99% of Biology We Can’t Touch

Cultivarium is Step 2.

The north star has been clear from the start: a new age of applied biology where we can understand and engineer any organism, of any complexity, in any domain. Right now, biology runs on less than 1% of life we’ve domesticated—mostly because DNA delivery, genetic tools, and engineering workflows break the moment you step off the familiar path.

The other 99%? You can look, but you can’t touch.

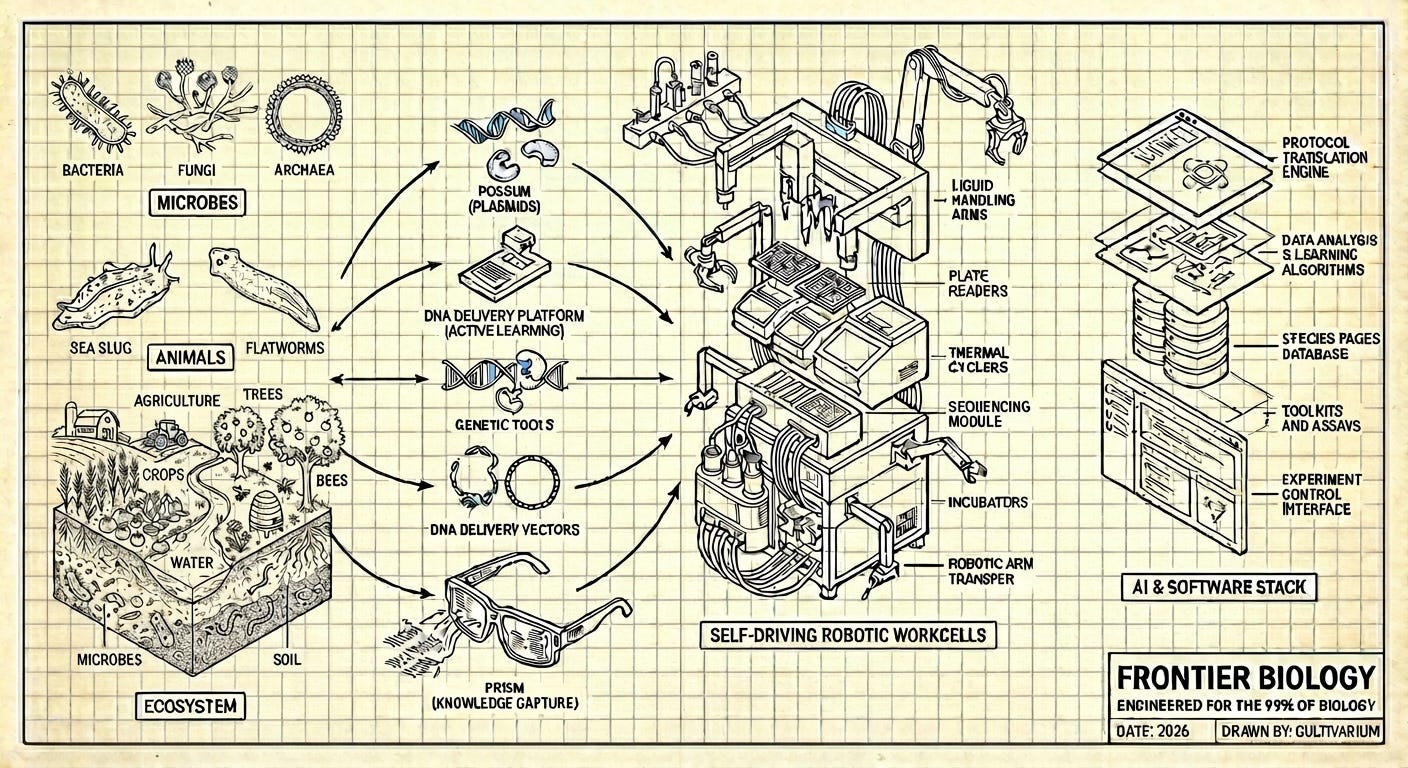

So the Cultivarium team built the capabilities we each wished we had. Brief highlights: POSSUM for systematic discovery of working plasmids. An electroporation platform with active learning that effectively teaches itself to get DNA into new organisms. PRISM for capturing experimental know-how multimodally. We have a full pipeline of projects and capabilities, including AI and robotics tooling, that we’re working furiously to make accessible for the broader community. We will have more to announce on this front very soon.

This has been—as microbiologists call it—our lag phase. Only in the last year have we started to bend into exponential growth, both in capabilities and in what we’ve learned about the space of non-model biology.

The Vomit Comet Problem

Internally, I’ve often described Cultivarium and these experiments in metascience as a vomit comet. It’s an amazing feeling while you’re suspended—the freedom and the means to build without the usual gravitational pulls. But weightlessness has a time limit. Eventually the parabola ends, and you must choose where you land.

Our choice reflects an uncompromising stance on the work we do:

If an effort is best as open-ended exploration, it belongs in academia.

If an effort can clearly recruit venture investment, it is best as a startup.

We continue to position Cultivarium’s work squarely in the vast gulf of foundational research—work that, when intensely built, has the ability to drive academic science and accelerate industrial applications. These are the genuine gaps in the R&D ecosystem: important work that needs to happen but that neither traditional path can sustain.

Some of the most impactful innovations come from non-model systems so we’re going to remain here in the trench and keep working.

A New Old Path: Frontier Research Contractors

This is why our next step—the Frontier Research Contractor (FRC) model—makes sense.

Today, we are announcing that we have joined the FRC Launchpad, a program run by Renaissance Philanthropy and supported by the UK’s Advanced Research and Invention Agency (ARIA).

FRC comes from a lineage worth knowing. ARPA’s biggest wins—the internet, autonomous vehicles, stealth aircraft—didn’t just come from good program managers. They came from exceptional contractors who shared three traits rarely found together: they were novelty-seeking, they built real technology for actual users, and they used more flexible team structures than academia allowed.

Bolt, Beranek & Newman (BBN) was one such contractor. They built the ARPAnet—not because they had the most funding, but because they’d spent years on adjacent contracts that positioned them perfectly when the opportunity arrived. They pursued an ambitious technical vision by offering their capabilities to others, productizing what made sense, and partnering where needed—without trying to fit an academic mold or pitch a market slide to venture capitalists before the science was ready.

An FRC operates the same way. We’ll keep pursuing our north star technical vision, but we’ll do it by building useful products for others along the way.

This is how we speciate. We’re making this mutation in our organizational DNA to give us a chance to adapt and thrive in the current environment. In a future post I’ll elaborate on what I think the “focused research” model got right and what comes next.

Why Now? The British Are Shooting Their Shot

My first conversation with ARIA was over a year ago. In the last few months, I’ve spent a lot of my time in the UK—learning from Science Conveners, chatting with Independent Scientists, discussing AI for Science, and having conversations from Cambridge to King’s Cross to White City.

My takeaway is simple: this is the most dynamic science ecosystem in the world right now.

There’s talk that UK science is “bleeding to death.” But that’s only because extraordinary talent and ambition are still pumping furiously. And there is hope: the UK is doing something the US isn’t—experimentation with its own innovation ecosystem.

ARIA embodies this. They’re trying new things, learning from them, and iterating—all with partners. And they’re doing it within their first three years. Contrast that with existing systems, even new ones, which are structurally opaque with little sign of movement. ARIA runs the equivalent of Fast Grants, ARPA Seedlings, and full DARPA-like programs. This is exactly the environment where experimenting with an FRC model makes sense.

I now see a boldness that I always associated with us. They’re doing science to win, whereas it increasingly feels like we’re playing to not lose. My fellow Americans, the British are coming. They’re shooting their shot. And I believe it will be heard around the world.

Through this program, Cultivarium will be looking for where our capabilities—DNA delivery, non-model genetics, protocol translation, AI-robotic experimentation—can serve ambitious new directions across ARIA’s Opportunity Spaces. We are going to play offense, and we’re gearing up to go earn it.

Open for Business

We’ll continue collaborating with academic labs, for-profits, and federal agencies. But we’re also opening our doors more deliberately.

We believe the real fruits of applied biology are yet to come, and reaching them requires building a taller ladder for everyone. That means working on the bottlenecks.

We’d love to see new types of organizations continue to spring up around us. More metascience experiments can be run so that we’re not all depending on subsidizing science through face creams and glowing plants. Critically, all efforts should be measured.

Cultivarium is a group of professional scientists and engineers unified to tackle the essential aspects of biological engineering. We seek the challenges that have been overlooked as underrated, too hard, and unglamorous, because we believe these are the things that must exist before the field can realize the full promise of engineered lifeforms.

This is our speciation event.

The mission hasn’t changed. The scope has expanded. And if we get this right, we’ll help unlock the 99% of biology the world still can’t touch to bring in the next age of applied biology. We’re certain that there’s a 100% chance it will be Not Boring.

We’ve spent four years building tools for organisms no one else could work with. Now we’re ready to build for anyone bold enough to try.