You Gotta Make It 'Til You Make It

Genetic tools for the most studied biocement organism on Earth

TL;DR (bioRxiv)

Sporosarcina pasteurii is the most studied biocement bacterium, but despite 70+ patents and decades of research, nobody had been able to genetically modify it

We report the first genetic toolkit: replicating plasmids, DNA delivery, promoters, reporters, and genome-wide transposon libraries covering 92% of genes

The breakthrough came from looking sideways—an environmental Sporosarcina relative helped us identify what works in the canonical strain

These tools convert biocement from a black box into a programmable system

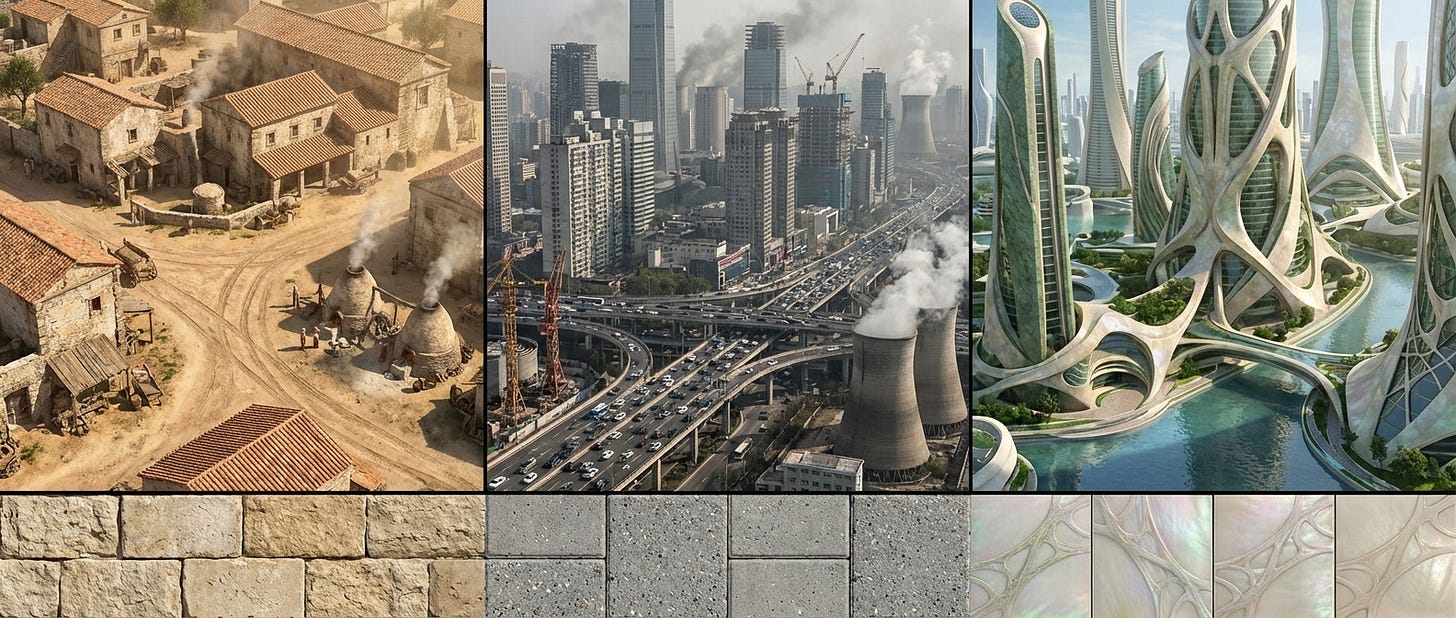

The Built World Has a Cement Problem

Cement is the third-largest emitter on Earth, trailing only China and the United States. Roughly 6–8% of global emissions come from a single material humanity can’t stop using.

We’ve loved cement since Roman times; it’s one of the most transformative materials humans have ever deployed. We’ve industrialized it so completely that every bridge, highway, and skyscraper carries a thermal and carbon history baked into the material.

So the world needs alternatives that deliver comparable strength and durability. And they must draw on lower-carbon inputs such as ground limestone, waste streams, agricultural feedstocks, or even urea.

That’s where biocement comes in—and with it, a strange little bacterium that’s been studied for decades but remained stubbornly out of reach.

The Microbe That Makes Rocks

Sporosarcina pasteurii is the most intensely studied bacterium for microbially induced calcium carbonate precipitation (MICP). Applications include sealing leaks in subsurface infrastructure, stabilizing soils and aggregates, forming alternative building panels and components. Feed it urea and calcium salts, and it precipitates calcium carbonate. Those minerals bind loose particles into stone-like materials. Biocement. And S. pasteurii has a set of traits that make it strangely perfect for the job: extremely high urease activity, tolerance to high pH and ammonia, the ability to form endospores for shelf-stable products, and negatively charged cell surfaces that nucleate calcite crystals.

More than 70 patents reference this organism. Researchers have worked on it for decades—yet it remained genetically intractable.

The Genetic Wall Nobody Could Break

At the American Society for Microbiology meeting earlier this year, a researcher summarized the state of the art:

“Unfortunately we have not been able to modify the organism in any way.”

This was a lab serious about biocement. They had built autonomous systems that spray cells and feedstocks over sand-like substrates, studied the biochemistry enough to identify putative urea transporters and carbon exporters, and explored how urea helps cells maintain osmotic balance. In other words: everything except genetic engineering tools. When asked what they’d do with these tools, the answers were immediate: modify urease to tune its kinetics, improve urea uptake, systematically knock out genes to understand how urea enters cells, how crystals form, how sporulation is triggered.

Genetics would be transformative but it remained unavailable. Without genetic tools, industrial efforts have relied almost entirely on process engineering—reactor tricks and adaptive evolution. Engineers can tweak conditions, but nobody can rationally engineer the biology. The field has been, you might say, set in stone.

The Soil Strain That Changed Everything

Here’s the twist: the breakthrough didn’t come from a new trick—it came from looking sideways. It wasn’t about banging our heads against the wall on the canonical 1889 strain. Cultivarium’s environmental isolations yielded a Sporosarcina relative that was unusually permissive to plasmid-based screening, and this environmental cousin helped us identify which genetic elements would function in S. pasteurii itself. The broader lesson is one we keep learning at Cultivarium: search the environment for engineerable variants, not just the textbook strain. The 99% of biology that exists outside model organisms isn’t just a source of new capabilities—it can also be the key to unlocking the organisms we already have.

Laying the Foundation

We report the first genetic toolkit for S. pasteurii: a replicating plasmid, a conjugation-based DNA delivery protocol, a panel of constitutive promoters spanning three orders of magnitude, synthetic inducible promoters, and fluorescent reporters and antibiotic markers. To show that the system works, we deleted the entire urease gene cluster—about 5.7 kilobases—eliminating urease activity and biocement formation entirely. We also built a genome-wide transposon library with more than 15,000 unique insertion sites across approximately 92% of genes, which has already revealed surprises: a transporter knockout that unexpectedly looks to improve growth on urea, hinting at genetic complexity the field hasn’t mapped, yet.

What We Can Build Now

With genetic tools, S. pasteurii becomes a true platform organism. Here’s some of what Cultivarium scientists have been most excited about: understanding and rationally engineering the fundamental biology of biocement formation, modifying ureolysis rates and reducing ammonia emissions, systematically mapping genotype-to-phenotype relationships with highly-multiplexed pooled libraries, and pairing genetic engineering with process innovations like green urea feedstocks and ammonia capture for fertilizer production.

But S. pasteurii is just the beginning. Making biocement useful and widespread will require solving many problems, and genetics is just the first enabling step. Genetics will help us study this fascinating biology in the detail it deserves—so that we can invent better solutions, not just tweak the ones we inherited.

Our hope is that this work inspires researchers across biology, materials science, engineering, and design to keep exploring how organisms can make desirable materials—and to help create a built environment that reinforces, rather than erodes, the ecosystems it sits on.

If you’re working on biocement, MICP, or biomineralizing microbes—and want to explore what’s now realistically possible with genetic engineering tools—reach out at partnerships@cultivarium.org

We’re collaborating with teams in materials science, biology, and industrial design who want to move this field past the limits of the last 30 years.

If you want more stories from the 99% of biology that never makes the news, subscribe to Off Media below.